Lavelle

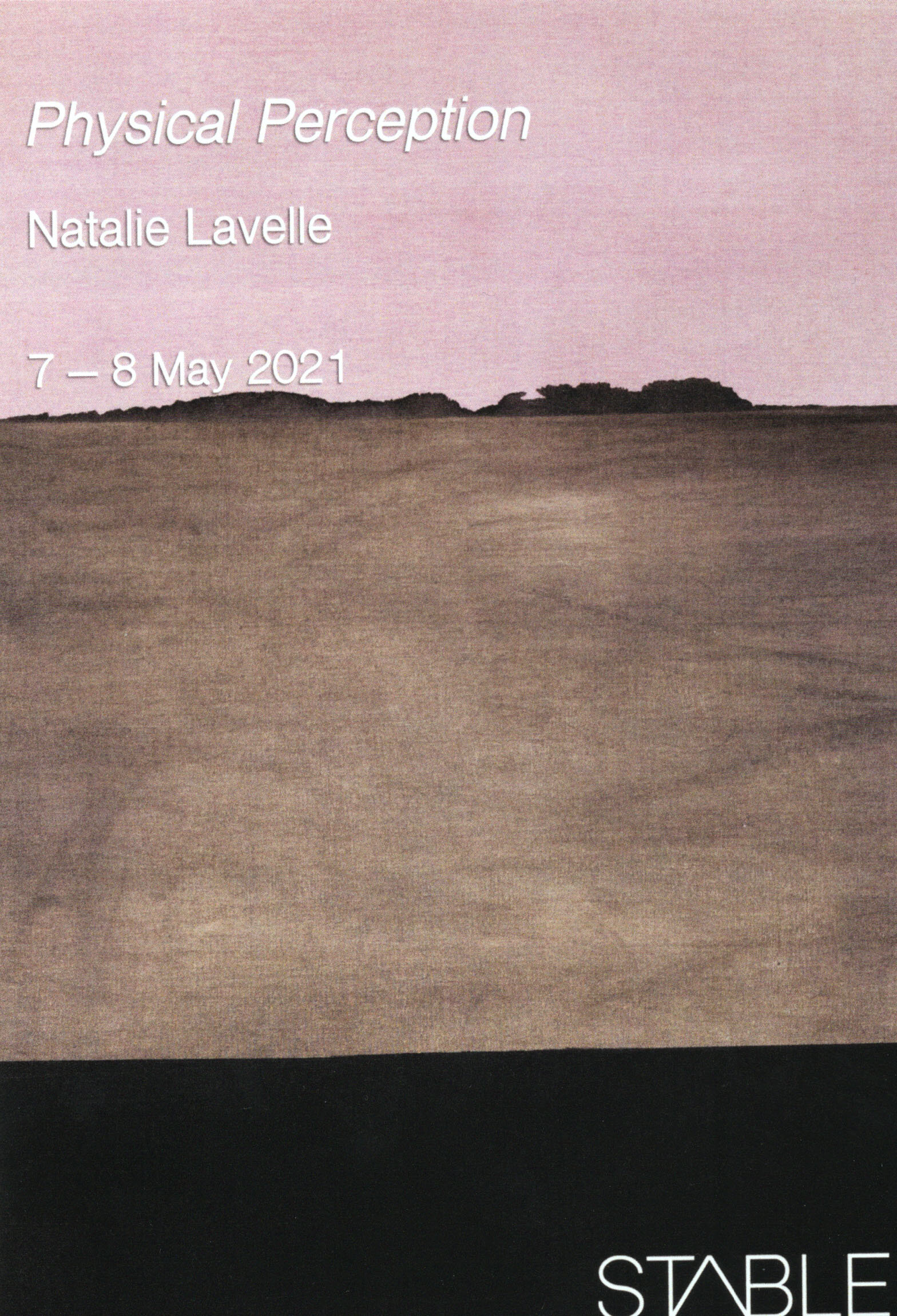

What I’ve always liked most about Nat’s work is its lack of pretence. By being entirely itself, it manages to be more than it is. And so, when Nat pitched me to write this essay in an email that included a prompt along the lines of “great art in ugly rooms” I couldn’t help but smile, because it was the exact kind of confidence and self-awareness one looks for in an artist you’d like to befriend. There are many artists, of course, whom one never wants to befriend, and they’re oftentimes the exact people you end up trapped speaking with at exhibitions. I recall one night in the last few years that I cannot place exactly, when I was speaking to someone about Nat’s work. They told me that her work seemed to expand—and this is paraphrasing, mind you—expand upon the theses of Abstract Expressionists as put forth by artists like Rothko, continuing a tradition of colour field painting that in a historical context now conjures up a post-war West when colours, it was felt, ought to be separate, ordered, arranged so as to be made sense of easily. Lavelle, this artist told me, despite knowing her first name, despite knowing that I knew her first name, Lavelle, he said, eschews the segregation once popular in this tradition and embraces bleed. She acknowledges, he said, that the ideal colour field is just that: an ideal, impossible, a thing best set aside in favour of the ambiguity that artists and not only artists—his voice now on the verge of a yell—that not only artists acknowledge, but also businessmen, and journalists, and even certain elected representatives. That’s why it’s good work, this artist explained as he tailed me to the bar where I then grabbed another wine or two, it’s good work, he said, because it puts forth a methodology for an honest relationship with the world. It instructs us to allow the organic to enact upon the canvas and to enact upon us. It says: you may choose the colours, yes, but as with so much of this world, you cannot control how they change; it is the way of things that they must bleed and seep and stain and collapse in on themselves to create the unique pigments that can be found only at overlap of those elements initially selected. You only have control over how you arrange the dominos, he said. How they fall is chance. It was shortly after this last comment that I finally managed to ditch him—though I do, as I write this essay, find myself considering his thesis. I wonder whether since that night he has gone on to become the foremost scholar on Natalie Lavelle, or whether he remains merely the foremost scholar on his own opinions about Natalie Lavelle, which is not the same thing at all. In the spirit of fairness, then, here is my opinion on Lavelle’s work: I think it is beautiful, and honest, and at once rough and delicate in a way that gestures toward aesthetic purity. I think the collection featured here in Physical Perception is as wonderful as any being produced in this town, and I adore most of all its lack of pretence, is what I’m trying to say.