On Seeing The Mural

I was at this party, one of those ones on the southside where you all stand around and talk as though you’ve all seen each and every artwork ever made. Each and every artwork, that is, except the ones anyone wants to talk about. That seems to be the rule at these parties: only one person per conversation is allowed to have seen the artwork being discussed—otherwise, it must not be worth discussing. And so when it was my turn to bring up an artwork, I decided to tell the story of the mural. It’s a story I usually tell when asked: How do you find living in Spring Hill? You know, in a suburb generally characterised by its littering of halfway houses, methadone clinics, and shuttered storefronts, by its bicycle thefts, its restaurants’ strange hours, and its anthemic screaming matches at two in the morning.

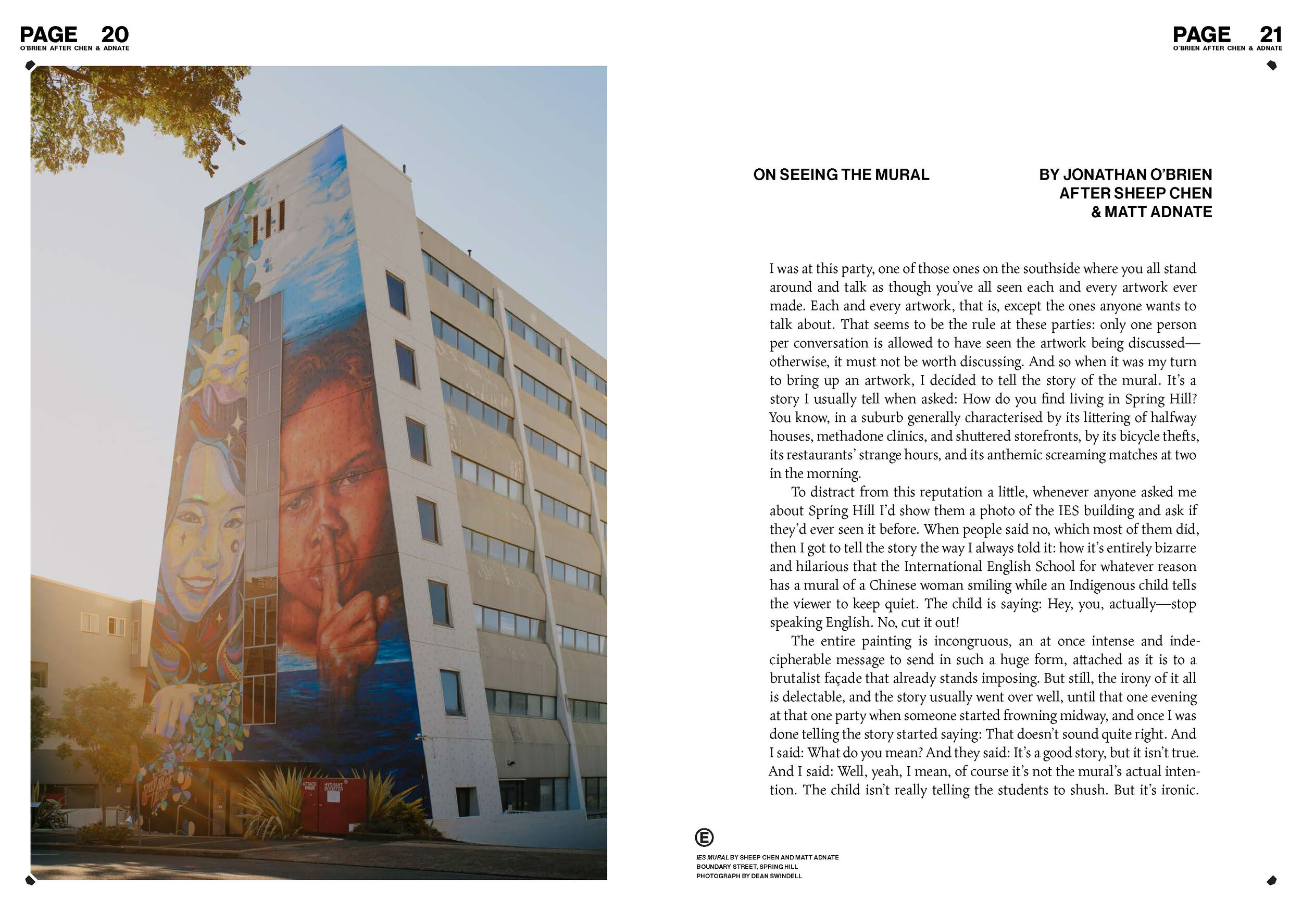

To distract from this reputation a little, whenever anyone asked me about Spring Hill I’d show them a photo of the IES building and ask if they’d ever seen it before. When people said no, which most of them did, then I got to tell the story the way I always told it: how it’s entirely bizarre and hilarious that the International English School for whatever reason has a mural of a Chinese woman smiling while an Indigenous child tells the viewer to keep quiet. The child is saying: Hey, you, actually—stop speaking English. No, cut it out!

The entire painting is incongruous, an at once intense and indecipherable message to send in such a huge form, attached as it is to a brutalist façade that already stands imposing. But still, the irony of it all is delectable, and the story usually went over well, until that one evening at that one party when someone started frowning midway, and once I was done telling the story started saying: That doesn’t sound quite right. And I said: What do you mean? And they said: It’s a good story, but it isn’t true. And I said: Well, yeah, I mean, of course it’s not the mural’s actually intention. The child isn’t really telling the students to shush. But it’s ironic. And they said: No, you’re being dishonest. And I said: No, I’m not; it’s true. And they said: How do you know? And I said: Because I see the mural every day. And they said: But how close have you looked, and do you know about Noni Eather? To which I said: I’ve looked close enough thank you very much; it’s just across the road from where I live, and no I don’t know Noni Eather.

At this, my interlocutor shook their head and let out a sigh. The rest of the group had excused themselves to get drinks, perhaps because they knew the one rule of the party had been broken: there wasn’t meant to be a dialogue, because dialogue meant the chance of conflict. And even though my drink was also empty, I was not free to leave. My interlocutor said to me then: Look, okay, for starters, the school is called IES College, and the IES stands for International Education Services. And even if it did stand for International English School, the mural wouldn’t really be ironic, because that young girl is a specific young girl who’s now a woman and whose name is Noni Eather, and she’s portrayed silencing the viewer as a tribute to the history of this place—the mural, after all, overlooks the Spring Hill’s Boundary Street. You’re not stupid; you know what that history means.

And I said: Sure, okay, sure, but don’t you think that it’s kind of silly to use this sort of imagery in front of a school? Don’t you think that this is a little too much context needed to understand such a public work of art?

And they said: I don’t know, maybe. Maybe it’s ill advised, and maybe it makes absolutely no sense. But even if that’s the case, it doesn’t mean you get to come in and spread misinformation based on assumptions you’ve made just so you get to seem clever or funny for a bit. Now, I’m gonna go get a drink. Do you want to come?

Much later that night, on the way home from my interlocutor’s house, I stopped by the mural. I saw then for the first time the plaque that explains the piece, featuring an excerpt from an interview with Noni Eather herself, whose father was a member of The Campfire Group, an artist collective once based out of a Torrington Street house, right nearby the IES College campus. In her words featured on the plaque, Eather explains that the reference photo for the mural, taken by Mick Richards in 1994, ‘became a symbol of [The Campfire Group’s] collective idea’. ‘Several artists,’ she says, ‘kicked off their solo careers there and together they generated projects for Indigenous education and cultural awareness.’

On reading this, the mural’s nature becomes clear to me: it serves as an invitation to a deep history, and it is this new clarity that renders my pithy story untellable. And while it feels bad to be corrected, and to part ways with one’s own easy answers, I have to remind myself that these feelings are selfish, and illusory, and that if art does indeed have a social purpose, then it is probably to teach us how to see, a task no work can complete if we refuse to meet it halfway, to at least try looking closely, in case there’s just a little more truth to be found.