The Conspirator: Cycle 07

Tess Mehonoshen’s Obstructing Loss

Tess Mehonoshen described the works she developed at House Conspiracy as ‘interventions’, and this word made sense for three separate reasons.

The first was that, by their nature, these folded up conglomerates of cotton, clay, concrete, and iron oxide could not last—both because of their fragility, and because they were site-specific, created during a residency that soon had to end.

The second reason ‘interventions’ made sense was that this combination of materials displayed in a traditionally domestic space—a house that had been home to a man named Len until a few days before we came in and tore up the carpet, painted the walls, and called it Conspiracy—left the materials feeling foreign. Certainly, the cotton muslin that was the skeleton of Mehonoshen’s work brought with it a domesticity, but any of that was near-unrecognisable by the end of the process, when the cotton was coated in industrial concrete, or in the clay she sourced from her family’s property out west.

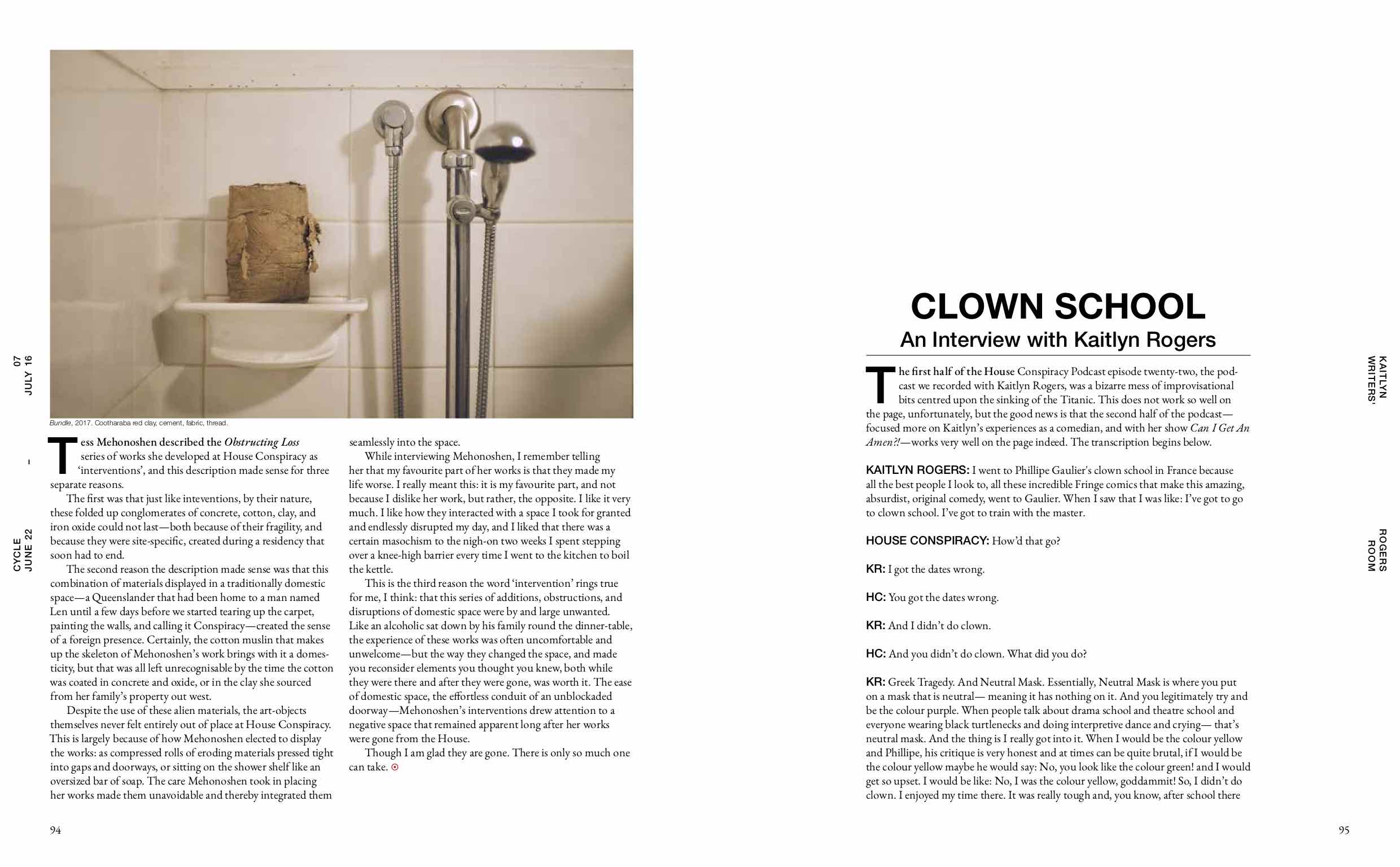

But despite the use of these alien materials, the art-objects themselves never felt entirely out of place in the House Conspiracy space. This is largely because of how Mehonoshen elected to display the works: as compressed rolls of eroding materials pressed tight into gaps and doorways, or sitting on the shower shelf like an oversized bar of soap. In this careful placement the work became unavoidable and integrated itself seamlessly into the space.

While interviewing Mehonoshen, I remember telling her that my favourite part of her works was that they made my life worse. I really meant this: it was my favourite part, and not because I disliked her work, but rather, the opposite. I liked them very much. I liked how they interacted with a space I took for granted and disrupted my day, and there was a certain masochism to the nigh-on two weeks I spent stepping over a knee-high barrier every time I went to go boil the kettle.

This is the third reason the word ‘intervention’ rings true for me, I think: that this series of additions, obstructions, and disruptions of domestic space were by and large unwanted. Like an alcoholic sat down by his family round the dinner-table, the experience of these works was often uncomfortable and unwelcome—but the way they changed the space, and made you reconsider elements you thought you knew, both while they were there and after they were gone, was worth it. The ease of domestic space, the effortless conduit of an unblockaded doorway—Mehonoshen’s interventions drew attention to a negative space that remained apparent long after her works were gone from the House.

Though I am glad they are gone. There is only so much one can take.

Clown School: An interview with Kaitlyn Rogers

The first half of the House Conspiracy Podcast episode twenty-two, the podcast we recorded with Kaitlyn Rogers, was a bizarre mess of improvisational bits centred upon the sinking of the Titanic. This does not work so well on the page, unfortunately, but the good news is that the second half of the podcast—focused more on Kaitlyn’s experiences as a comedian, and with her show Can I Get An Amen?!—works very well on the page indeed. The transcription begins below.

KAITLYN ROGERS: I went to clown school in France because all the best people I look to, all these incredible Fringe comics that make this amazing, absurdist, original comedy, went to Gauliere. When I saw that I was like: I’ve got to go to clown school. I’ve got to train with the master.

HOUSE CONSPIRACY: How’d that go?

KR: I got the dates wrong.

HC: You got the dates wrong.

KR: And I didn’t do clown.

HC: And you didn’t do clown. What did you do?

KR: Greek Tragedy. And Neutral Mask. Essentially, Neutral Mask is where you put on a mask that is neutral— meaning it has nothing on it. And you legitimately try and be the colour purple. When people talk about drama school and theatre school and everyone wearing black turtlenecks and doing interpretive dance and crying— that’s neutral mask. And the thing is I really got into it. When I would be the colour yellow and Phillipe, his critique is very honest and at times can be quite brutal, if I would be the colour yellow maybe he would say: No, you look like the colour green! I would get so upset. I would be like: No, I was the colour yellow, goddammit! So, I didn’t do clown. I enjoyed my time there. It was really tough and you know, after school there was one time I went for a jog because school was in this village in southern France and we were surrounded by a forest and after school every day I would go for a walk in the forest or go for a jog and on the good days I would go for a jog and I would be running through the forest saying: Oh, I’m so free! Anyway, one of those days I was feeling great I ran and I climbed a tree and fell out and cracked a rib. The next day I had to do neutral mask and pretend to be glue. I couldn’t do it.

HC: Because you weren’t together.

KR: No, I wasn’t. I needed glue. Because I was there for first semester I was lucky enough to do Play which I was really glad to be there for because it’s about tapping into the part of the brain that adults lose track of which is play and imagination. Kids do this naturally. Phillipe’s teachings are all based in play and based in pleasure and having genuine fun when you’re onstage. The way he teaches that, the first exercise we did at Phillipe’s school was, he said: Okay, so you go on the stage and you have a suitcase and in the suitcase is a fish and you walk around and you walk around and all of a sudden you go Bah! I am in Vietnam! Go.

HC: That’s the first exercise?

KR: You have no idea what to do. You go up and pretend to have a suitcase and he would smash his little drum saying: No, no, no! You do not get my exercise. Get off my stage! And then another group would go and they wouldn’t get it. He would say: Oh, you’re such buyers of shit! I want to kill you. We all want to kill you! Then four or five rounds in its actually apparently about having fun. The whole first half of school was learning what Phillipe was talking about. You cannot take what he says literally. Everything has a different meaning to what he is actually saying. Once you understand that. Once you embrace it that’s the play. That’s the fun. Once I realised that, I had a really good time.

When he says: You have a suitcase and there’s a fish in Vietnam. What he means is: You’re in an absurd situation that has a lot of discovery in it and have fun with those feelings. Or, did you still have to get up and act those things but act in a fun way?

I think the thing about any teaching, I suppose, is you interpret it in your own way especially for Phillipe. You see from past students that they have taken something from him he has given. My interpretation is the first thing you said. It’s about being present onstage but not only present, having fun. And that little sparkle in an actor’s eyes when they’re on the stage and they’re truly there whether they are crying or screaming or laughing. You can see that joy in play. Again, you see it in kids when they play cops and robbers and they’re shooting each other and they die and they’re going Pew! Pew! Pew! Pew! Pew! They’re having the best time even though in reality it’s something quite violent. I think for me, over the years, because I have worked in a hospital and because I have travelled through places that are quite traumatic I feel my sense of comedy is warped in that I find things hilarious that some might think are weird.

HC: So, it’s about the framing of a situation and the feeling rather than the thing itself.

KR: Everything is context, you know? You can be in a situation but how you play the situation— there’s such a spectrum there. There’s so much to play with. For me, what interests me, is playing with things typically seen as being darker but playing them light. The contrast and tension between tragedy and comedy interests me. I have a lot of fun playing with tragedy in a comedic sense.

HC: Which leads quite well into your show: Can I get an Amen?!, an award winning, um, one woman comedy show.

KR: Still nobody knows what it is and neither do I.

HC: Let’s talk about that. In your application, the way your show was presented is maybe different to the way you’re perceiving and talking about it now. Maybe you could talk about how and what it was in its Short+Sweet Festival run and then what it’s become now and why it’s become that.

KR: I guess it’s definitely evolved over time and I already know it’s going to continue to evolve. There’s a difference between what the show is based on and where it started because years ago when I was living overseas and going through quite a tough time I kept a journal. Essentially, when I came back to Australia, after being away for so long and going through some rough stuff I was so happy to be home and something that really clicked in my brain was just how great it was to be home in Australia and I’m so grateful for the quality of life we have here and that kind of fuelled and informed a time of… good fucking times. I was lucky to be surrounded by really cool mates and just enjoy the beach and the simple things. And it was from that time of simplicity and just chilling the fuck out I started to make rumours up about myself.

I started to do stand-up which was a Band-Aid for a while. When I did stand-up for the first time I did it at a place that’s famous for being the worst place on earth to do comedy. A place where you can sometimes have glass thrown at you. It no longer exists. It was on the north side. I started doing stand-up. I always wanted and dreamed of doing The Fringe, I worked The Fringe overseas, I did Edinburgh ages ago. It was always my goal to end up there. I did a show. I played an Australian dinosaur. I was a puppeteer. The company’s called Earth and they had this incredible show called Dinosaur Zoo and I was lucky enough to go on the West End in London. We did a UK tour and then we did the Edinburgh Fringe for the whole month and we were in the stadium. That was a family show but in doing that I was able to experience that Fringe life which is the Mecca of the theatre and everything in-between: comedy, cabaret, everything. Everything is there. The buzz is intoxicating and incredible. That month was the best month of my life going: I’ve got to come back here. I’ve got to do my own show one day.

When I started doing stand-up I started looking at who’s really awesome. Who do I really love? I went to Adelaide and that’s when I started a rumour about myself. At that point I had the title which was: Can I Get an Amen?! I water-coolered myself. I would stand by water-coolers and say: I hear that Kaitlyn Rogers has a really funny show called Can I Get an Amen?! I said I had a show when I didn’t. I kept saying I had a show. It came to a point where I needed to do something about it. That’s where Short+Sweet came into the pie. Because I saw it as an amazing opportunity. It was only ten minutes. If I put something out there and if it fell on its face then I could move on. But I took this as an opportunity to put something out there I really enjoyed doing. It was at the Powerhouse which is such a fantastic venue and the team behind Short+Sweet are so supportive of artists. You can just concentrate on creating work. You don’t need to worry about producing, which is another thing in itself which is so demanding and it’s just a completely different full-time job. To be able to be given the chance to solely focus on the creative side was really fantastic and that’s when I went into a process. I never really created anything by myself before. I locked myself in a room and tried to make myself laugh for about six months. I put together this collection of things I think are funny. It always started from a physical place because I love moving and grooving. I’ll kind of dance around to gospel music. And then do weird things with my body and improvise off of that and then the text would come last.

Following her development at House Conspiracy, Kaitlyn Rogers took Can I Get An Amen?! to Edinburgh Fringe, and then to Fringe World and Adelaide Fringe. The show has been a success everywhere it has gone.

Holly Anderson’s Seance

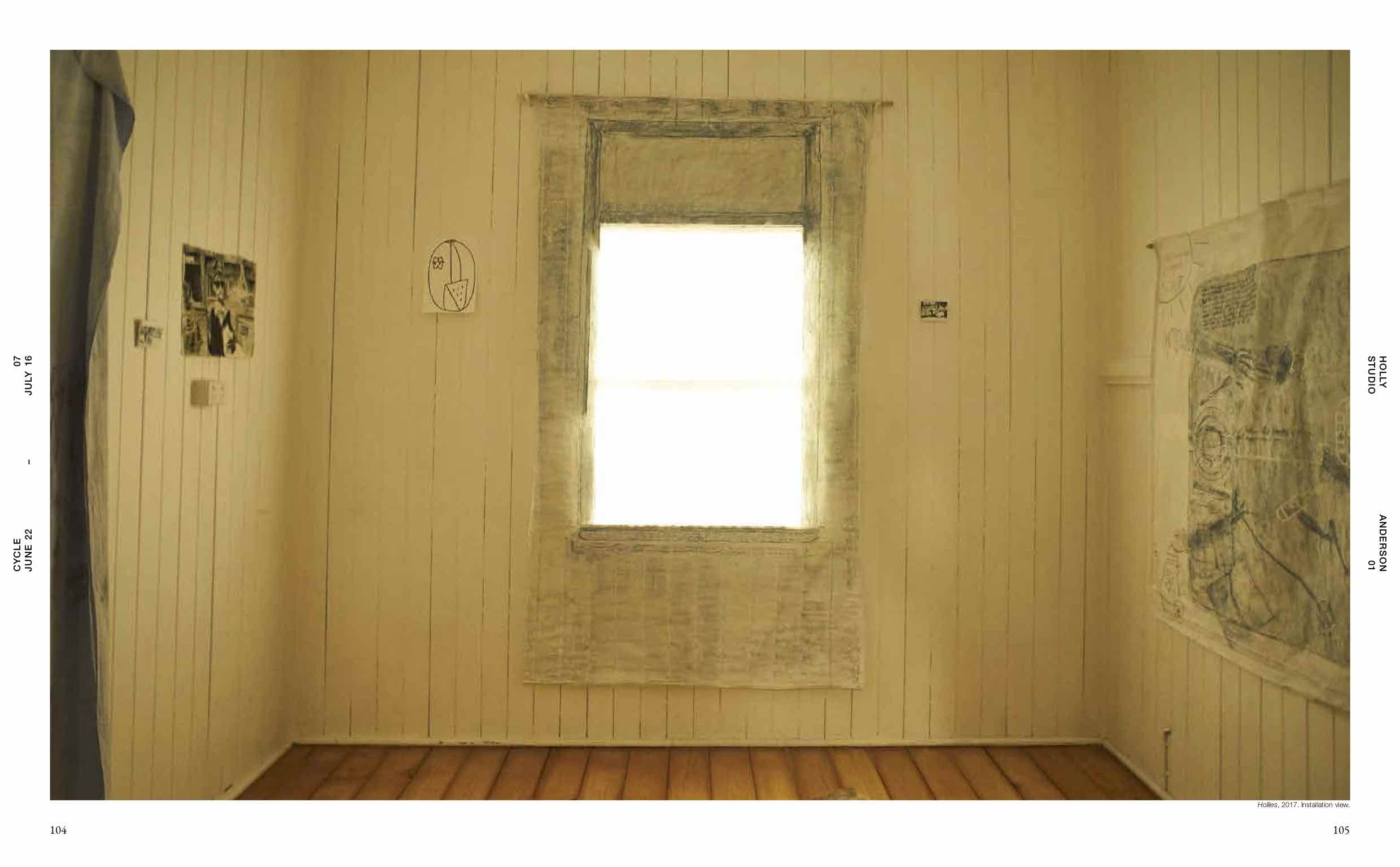

During her time in Studio 01, Holly Anderson staged a haunting. Her studio, she explained to Her studio, she explained to me, was occupied by a spirit—the spirit of Audrey Hepburn’s Holly Golightly, from Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

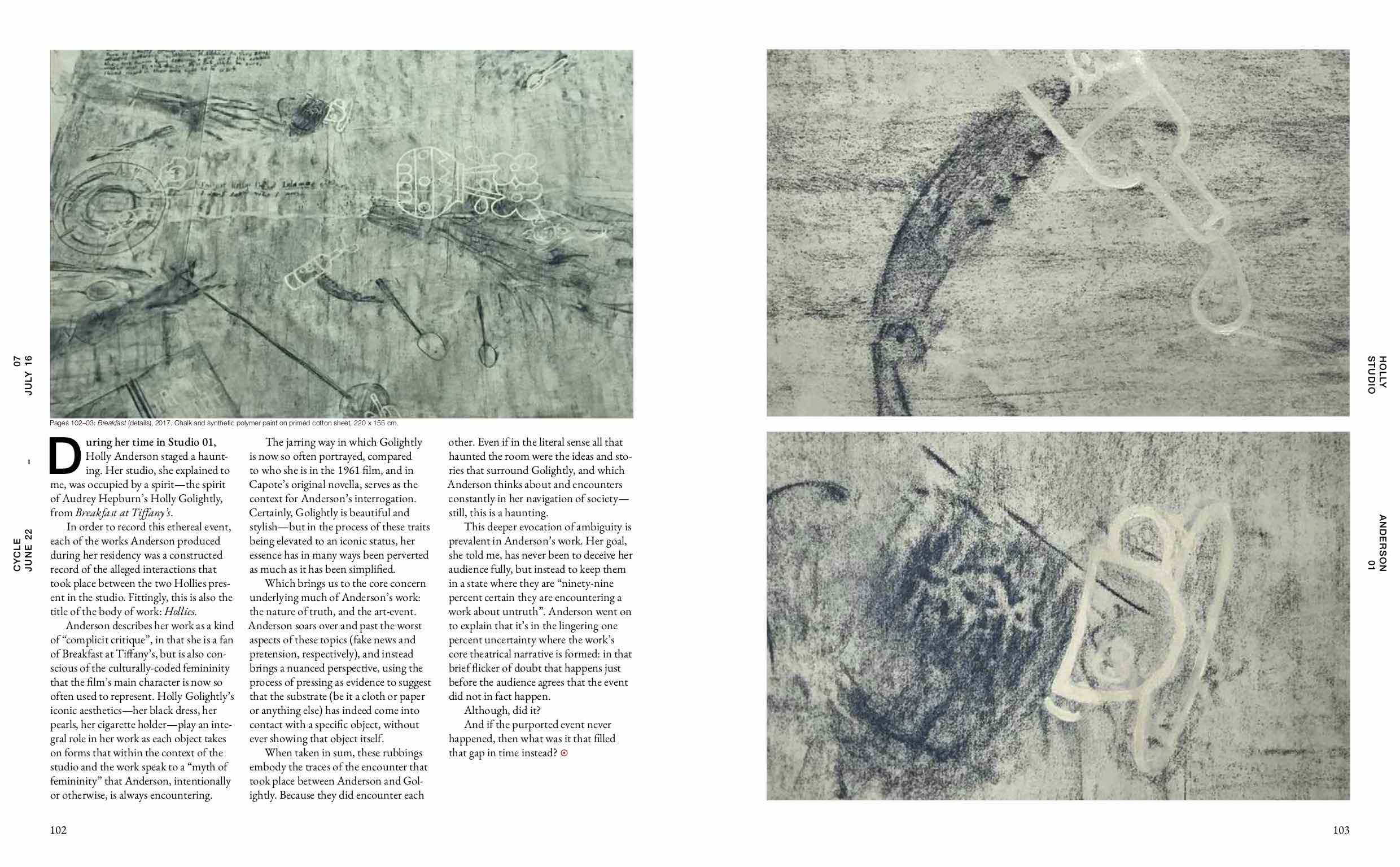

In order to record this ethereal event, each of the works Anderson produced during her residency was a constructed record of the alleged interactions that took place between the two Hollies present in the studio. Fittingly, this is also the title of the body of work: Hollies.

Anderson describes her work as a kind of “complicit critique”, in that she is a fan of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, but is also con- scious of the culturally-coded femininity that the film’s main character is now so often used to represent. Holly Golightly’s iconic aesthetics—her black dress, her pearls, her cigarette holder—play an inte- gral role in her work as each object takes on forms that within the context of the studio and the work speak to a “myth of femininity” that Anderson, intentionally or otherwise, is always encountering.

The jarring way in which Golightly is now so often portrayed, compared to who she is in the 1961 film, and in Capote’s original novella, serves as the context for Anderson’s interrogation. Certainly, Golightly is beautiful and stylish—but in the process of these traits being elevated to an iconic status, her essence has in many ways been perverted as much as it has been simplified.

Which brings us to the core concern underlying much of Anderson’s work: the nature of truth, and the art-event. Anderson soars over and past the worst aspects of these topics (fake news and pretension, respectively), and instead brings a nuanced perspective, using the process of pressing as evidence to suggest that the substrate (be it a cloth or paper or anything else) has indeed come into contact with a specific object, without ever showing that object itself.

When taken in sum, these rubbings embody the traces of the encounter that took place between Anderson and Golightly. Because they did encounter each other. Even if in the literal sense all that haunted the room were the ideas and stories that surround Golightly, and which Anderson thinks about and encounters constantly in her navigation of society— still, this is a haunting.

This deeper evocation of ambiguity is prevalent in Anderson’s work. Her goal, she told me, has never been to deceive her audience fully, but instead to keep them in a state where they are “ninety-nine percent certain they are encountering a work about untruth”. Anderson went on to explain that it’s in the lingering one percent uncertainty where the work’s core theatrical narrative is formed: in that brief flicker of doubt that happens just before the audience agrees that the event did not in fact happen.

Although, did it?

And if the purported event never happened, then what was it that filled that gap in time instead?

O'Brien, J. (Ed.) (2018). The Conspirator. 1st ed. Brisbane: House Conspiracy Inc. (ISBN: 978-0-646-98615-9)